Have you ever met your end at the hands of a staircase? Not a ferocious dragon or a cunning boss, just a simple misstep. You fall, see that dreaded “You Died” screen, and suddenly it’s back to square one. Frustration mounts, the controller might get tossed aside, but you know what? You always come back. Because in that space between embarrassment and the thrill of victory, there’s a triumph that no amount of microtransactions can buy. We’re talking about players who never forgive, and yet, we’re the ones who willingly dive back into the fray.

Pain as a Teacher

The reason we love these punishing games is simple: they give us something that others don’t, an overwhelming sense of accomplishment. It’s not about luck or hand-holding, it’s about enduring hardship, failing repeatedly, and still standing strong. These games don’t hold back, and that’s why their victories feel genuine. The joy comes from the struggle, the agony, the cries of despair, and ultimately, the triumph of making it through.

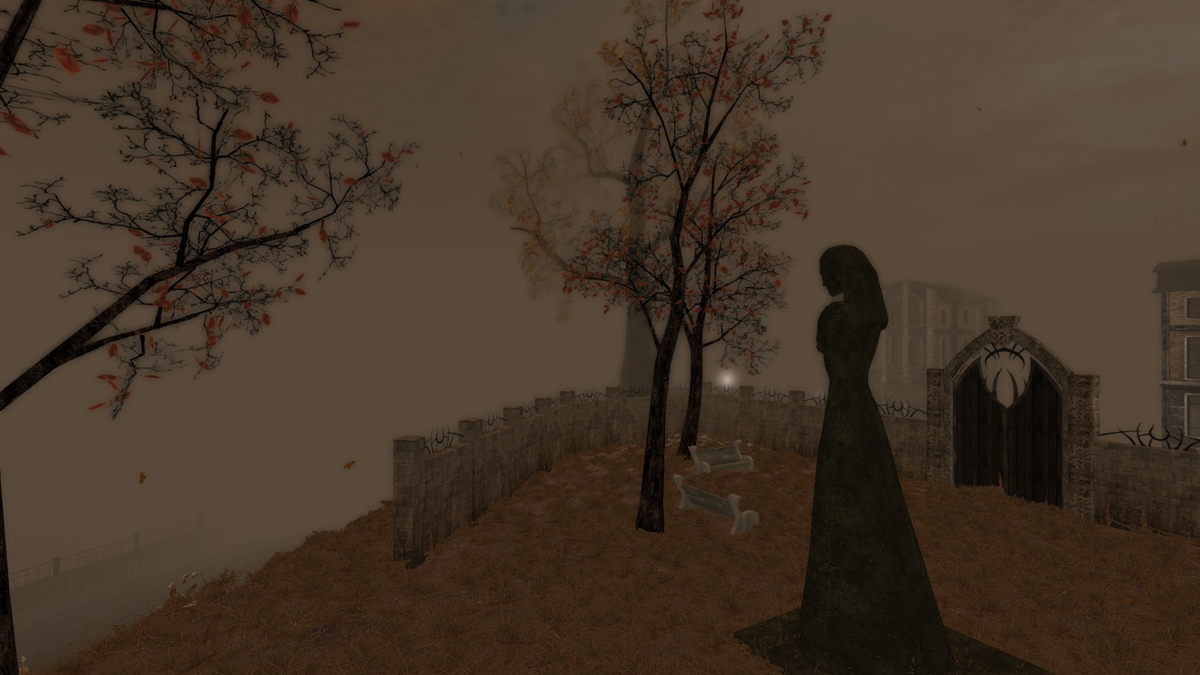

When it comes to titles from FromSoftware, think Dark Souls, Sekiro: Shadows Die Twice, Bloodborne, and Elden Ring, death is not just a “whoops, wrong button.” It’s an essential part of the experience. Died again? Fantastic! You’re one step closer to overcoming that challenge. Welcome to a world where failure is currency, and suffering is the primary language.

The Souls series doesn’t just ramp up the difficulty, it strips away the fluff. Forget quest markers, pop-up tips, and NPCs offering hugs after you fail. Here, even the story speaks through pain. You don’t start as a hero, you begin as a rotting corpse armed with a stick and a shred of dignity. But if you endure, learn, and grow, you might just find yourself battling gods on even terms.

At first, it’s terrifying. Then, it’s infuriating. But then comes that glorious moment when the boss you feared like a tax audit crumbles under your blows. No cutscenes, no fanfare, just silence, a soul that falls, and that indescribable feeling: you did it yourself. Not because the game went easy on you, but because you leveled up.

And this isn’t just a Dark Souls thing. In Sekiro, the game demands you adapt. You can’t just level up your armor or spam attacks, you have to master parrying until it becomes second nature. And what about Elden Ring? It’s like stepping into an open world where friendly smiles often lead to a punch in the face. Where freedom becomes a trap, and curiosity pulls you into the jaws of a demigod. Even Demon’s Souls, the one that started it all, doesn’t offer an ounce of mercy, posing the question: “Are you really ready?”

This is the fundamental thrill of Soulslike games, the moment you stop being afraid. The game hasn’t gotten easier, you’ve transformed into someone who doesn’t crumble at the first hit. You remember patterns, spot weaknesses, and learn from your blunders, not through scripts, but in real-time.

Hidetaka Miyazaki, one of the genre’s founding fathers, once said: “Death in our games serves as a tool for learning through trial and error.”

FromSoftware has crafted a new aesthetic, pain is beautiful, the world is silent, the narrative is buried under layers of fragments, and triumph comes not from victory but from the journey toward it. It’s not hardcore for the sake of being hardcore, it’s about you, in a world that owes you nothing. That’s why we keep coming back, not because we enjoy suffering, but because after enduring the pain, we finally feel like our achievements are earned.

Suffering as a National Idea

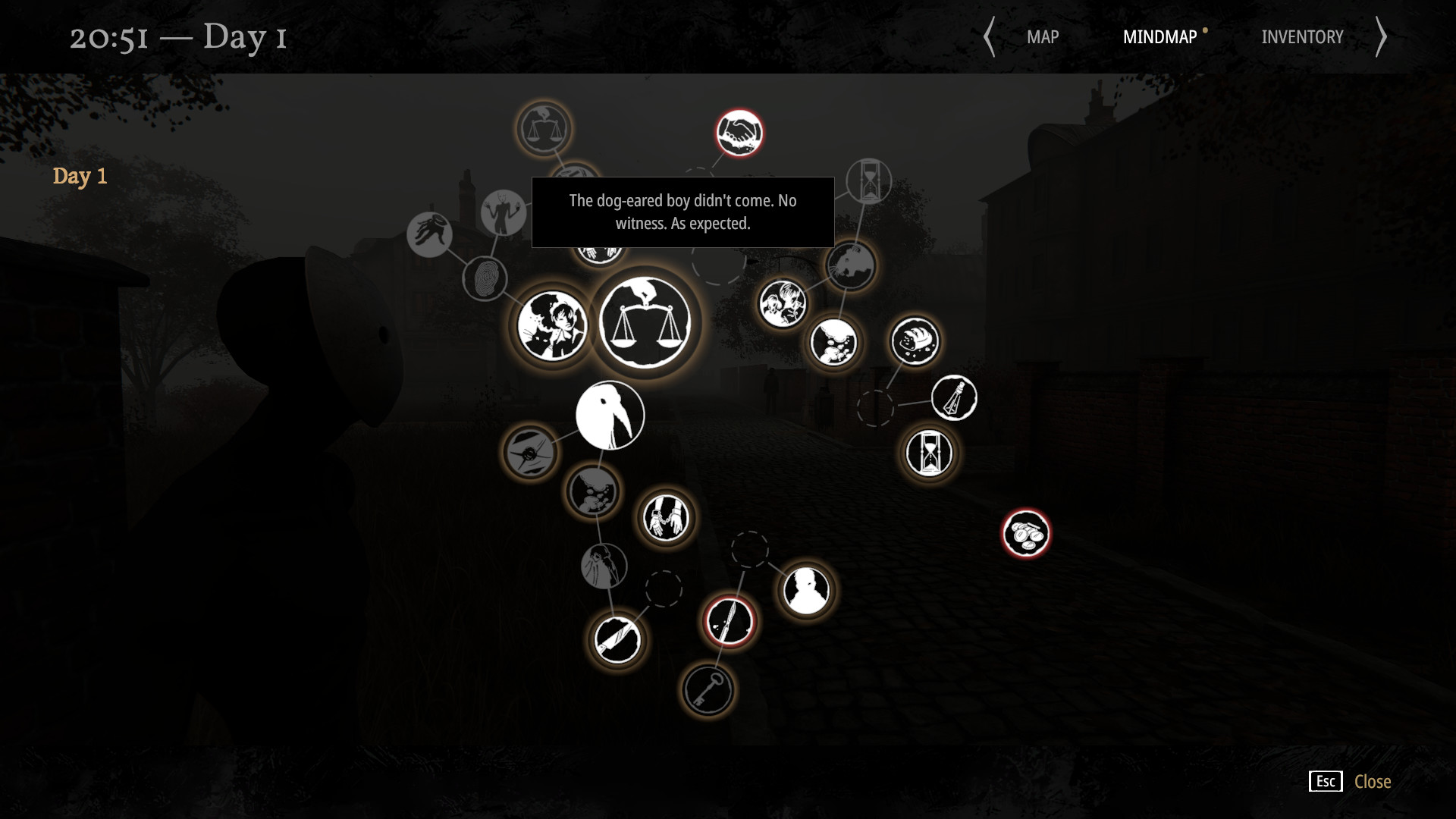

Dark Souls teaches through suffering, while Pathologic makes pain your constant companion. This isn’t a game where you die and just move on. This is a game where living itself becomes a punishment. Welcome to the City-on-the-Gorkhon, which literally decays before your eyes. Where bread is worth more than life, water is a commodity, and every minute costs someone their existence.

Released in 2005 by the Ice-Pick Lodge, Pathologic boldly declared: “Guys, no comfort here.” You’ll have everything except a sense of security. Disease roams the streets. People are dying. Pharmacies are empty. You’ve got a knife, a vial of analgesics, a dubious reputation, and just twelve days to save everyone.But you won’t be able to do this, it’s not a bug, it’s a feature.

Ice-Pick Lodge didn’t just create a game, they built an experimental environment to test you.“Pathologic” is about how helplessness becomes the norm. You’re a doctor trying to save lives, but all you can offer is a spoiled bandage and crumbling pills.

Feeling terrible? Great, that means it’s working as intended. In this game, emotions aren’t a side effect, they’re the designer’s goal. You need to feel despair. You must fear sleep because it’s a waste of time. You look at your half-empty inventory like it’s a will. Eat the bread or leave someone hungrier? Buy a bandage or bury your hopes?

Here’s where Pathologic breaks the classic narrative: you’re not a great savior or even “the chosen one.” You’re a cog in a dying system. The storyline branches like a vascular system during an autopsy. Every choice isn’t about “right or wrong,” but “who suffers more.” Save the child, and your friend dies. Feed a familiar, and you starve. Morality in Pathologic is a luxury you can’t afford. The game tells you: “You won’t do it right. But you must act.”

The sequel, Pathologic 2, cranks up the intensity while also being more beautiful. It doesn’t just maintain tension, it crushes you. A vast, breathing city where every day is a fight for survival. You go to sleep hungry, wake up too late, someone’s dead, someone’s sick. Quests burn away like homes in quarantine. The game doesn’t let you “win,” it lets you resist for as long as possible.

The most terrifying aspect of Pathologic in both parts and a third installment is on the way isn’t death itself, but its inevitability. People die regardless of your efforts, you won’t catch up. The game doesn’t allow you to be an omnipotent hero unlike in Soulslike games, where with enough practice, you can become one. It shatters that very fantasy. Here, you aren’t the center of the universe, you’re a person, tired, hungry, burdened with guilt that only grows stronger with each passing day.

And that’s the main psychological blow. You do everything right, but endlessly lose. Because the world is unfair, resources are scarce. Because saving one person means letting another down. And this impossibility of a “good ending” isn’t mockery, it’s a truth of life. It’s essential to note that this isn’t done for the sake of hardcore gameplay, but for atmosphere. Pathologic is not an action game, a drama, or an RPG. It’s a philosophical horror, a theatrical performance where the set crumbles, the actors whisper about meat, and the theater itself is built from pain. Ice-Pick Lodge didn’t aim to create a game in the traditional sense, they crafted an experience that is rotten and suffocating, but alive.

Here lies the paradox: when you survive and find someone you’ve helped, you feel it was not in vain. You haven’t saved everyone, the city will still die, but you didn’t give up and that is a victory, quiet and personal without fanfare. As it should be in a world where every choice is always between the bad and the far worse.

And you know what’s surprising? Players keep coming back, not because it’s fun but because it matters. Because in a world that wants everything simplified, “Miasma” dares to speak the truth: sometimes you can’t win but you can stay human, and that alone is no small thing.

Pixel Hell with a Philosophical Twist

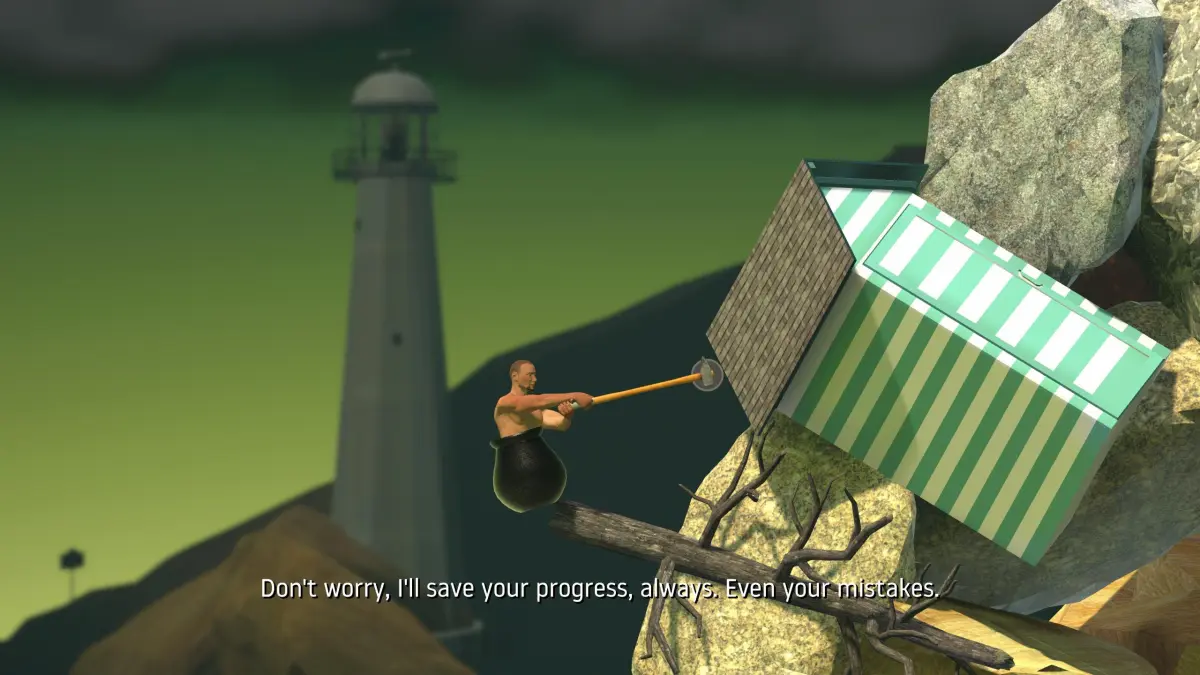

Ever feel like video games have cornered the market on epic misery? After slogging through Dark Souls or getting lost in Pathologic’s grimy, plague-ridden world, you might assume that any “hardcore” title has to come swathed in orchestral music, Gothic castles, or cryptic philosophical monologues. Guess again. Enter Getting Over It with Bennett Foddy, a game that strips away everything except a naked guy trapped in a cauldron, armed only with a gigantic hammer.

No bosses. No sprawling levels. Just you, your hammer, a junk heap of refrigerators, tree limbs, and utter despair… and Bennett’s soothing yet slightly smug commentary echoing in your ear as you plummet to your death for the umpteenth time.

When Pain Is the Point

Most tricky games teach you progression: gear up, level up, overcome a big bad, and finally feel like a badass. In Dark Souls, each brutal boss fight and inevitable death is framed as a lesson. You die, you learn, you adapt. When you conquer that boss, it’s not “just a win,” it’s proof that you’ve absorbed the lesson. Pathologic doubles down on this grim concept, flinging you into a decaying town where starvation, sickness, and moral quandaries assault you from all sides. It’s heavy, it’s immersive, and each setback feels “fair” because it’s woven into the story: you’re meant to feel powerless, as your character literally is powerless.

With Getting Over It, though, there’s no storyline to justify your suffering. No character arc, no loot drops, no gradual stat boosts, just the pure, unfiltered agony of trying to climb a pile of garbage with a hammer that might as well be greased lightning. You slip, you fall, you hear Bennett Foddy’s next zingy philosophical quip (“The harder you fall, the farther there is to climb,” etc.), and you’re back at the bottom. Over, and over, and over.

Yet, somehow, voluntarily torturing yourself on that mountain of random detritus can be cathartic. Psychologists point to cognitive dissonance and the weird thrill some people get from safe, controlled suffering. Call it “pain as a point,” or “self-inflicted frustration therapy,” or just “Why am I playing this again?” Either way, there’s a strange, compulsive loop: you fail, you feel dumb, you hit Retry. You swallow the seed of hope that “this time you’ve got it.” And even as the hamster wheel spins, you’re secretly proving to yourself “I can survive this, I can endure.” It’s less about beating the environment and more about facing your own impatience, pride, and stubbornness.

Souls vs. “The Cauldron–man”

At a glance, Getting Over It feels like Dark Souls’s lazier, nudist cousin. Both games weaponize pain and both make victory taste sweeter by making defeat so bitter. But their philosophies diverge. Dark Souls says, “Get stronger. Learn enemy patterns. You will prevail.” You grind, you improve your character, you build a strategy. The suffering has a purpose: growth. Getting Over It whispers, “Here’s a hammer. Here’s a mountain. Go make sense of gravity.” Your only upgrade is your own temper or lack thereof. There’s no character profile, no enchantments, no narrative, therefore no outside motive to improve other than the desire to demonstrate your capability.

This makes Getting Over It a sort of stripped-down psychological experiment, it’s about facing failure in its purest form. You keep smashing that pot, fumbling that swing, miscalculating your grip, and Bennett’s voice reminds you, in chilly philosophical tones, that any stumble is your own carrying. It’s akin to “exposure therapy” in psychology, you willingly expose yourself to the fear of failing and falling, over and over, until the anxiety flattens out and you learn to roll with it. Instead of a narrative that holds your hand, you have your own frustration to contend with, no checkpoints, no easy-outs. Just “Retry” as the ultimate test of resolve.

When Challenge Becomes Cruelty

So how do you tell the difference between a “fair but brutal” game and a “sadistic waste of time”? It boils down to meaning. In a well-crafted challenge, say a Souls boss in a castle built around learning enemy tells, you die knowing “I messed up, but I know why.” You can plan a critique of your approach, “Next time, I’ll lock on sooner,” or “I shouldn’t spam that roll.” There’s a clear, albeit steep, path from ignorance to mastery.

Now imagine a “Kaizo” level in Super Mario Maker where the timing for a jump is so absurdly tight that even if you nail it perfectly, some invisible random pixel will still murder you. No clue why, no consistency, no pattern. Or think of those relics from the 8-bit era where screen edges would spawn enemies exactly when you land from a jump, guaranteeing death even though you played flawlessly. That’s not “challenge” at all, it’s “damage on a whim.” The game isn’t testing your skill, it’s just out to humiliate you.

That’s the fine line between “Hey, you gotta git gud” and “Ha, I win.” A truly tough game arms you with feedback loops and incremental skill checks (e.g., Souls, Celeste, Sekiro, modern roguelikes), so that every death still feels like a stepping-stone to eventual victory. A sadistic game withholds those essentials. If you die, it’s because it decided to mess with you, not because you neglected to master the mechanics.

Examples of Unjust Hardness

Kaizo Super Mario Maker

Purists love sharing videos of run-after-run ending in invisible blade doom, yet most players call it out: “That’s not skill-check difficulty, that’s pure ‘gotcha!’ trolling.”

Retro Platformers With Unseen Spawns

You land, boom, an enemy appears out of thin air. You had zero reaction window, the game just yanked your rug away.

Randomized Mob Spawns in certain old-school RPGs

One moment you’re cruising, next moment a horde of invincible foes spawns behind you with no warning, instant Game Over, rinse, repeat. “Fair?” Hardly.

The unifying factor in these “pain for pain’s sake” designs is a lack of honest communication. They hide their rules, offer no counterplay, and leave you feeling like a lab rat in a cruel experiment. In contrast, in great hardcore titles, even ones drenched in misery, you can usually point to the moment the game explicitly telegraphed its intention. You misread the warning, you jumped a split second too late, and you think, “All right, next time I’ll be ready.” The cycle can be brutal, but it’s not abusive.

Why We Chase the Agony

Still, there’s something addictive about this brand of challenge. Whether it’s Dark Souls, Pathologic’s relentless starvation timers, or a cauldron-dwelling man with a hammer, these games probe your ego. They question your expectations of “fun” by taking away control, stripping away comfort, and confronting you with the possibility of repeated public embarrassment, thanks to YouTube compilations. Yet, most of us come back for more because when you do finally succeed, beat that boss, survive another day in the plague-ravaged town, or wedge that hammer just right so you inch upward, that victory feels like your own personal revolt against chaos.

In a world increasingly obsessed with accessibility, auto-saves, and adaptive difficulty sliders, these uncompromising experiences remind us that growth often comes from pain. They whisper or bellow, “Not everything in life is supposed to be easy.” And yes, sometimes you’ll scream, “Why am I doing this?!” But if you stare down the abyss often enough, be it in a Souls boss arena, Pathologic’s deserted streets, or atop a tower of busted microwaves, you might just discover a sliver of satisfaction that’s impossible to replicate with a quick button-mashing handhold. Because that sweet, hard-won triumph on the other side belongs exclusively to you. No restart can take that away.

Share this: